Saturday, June 16, 2018

Features

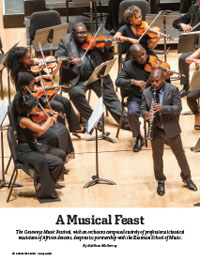

A Musical FeastThe Gateways Music Festival, with an orchestra composed entirely of professional classical musicians of African descent, deepens its partnership with the Eastman School of Music.By Kathleen McGarvey

IN PERFORMANCE: Anthony McGill, the principal clarinetist of the New York Philharmonic, took center stage at the 2015 Gateways Music Festival, playing a concerto with the festival’s orchestra. (Photo: Keith Bullis for University Communications)

IN PERFORMANCE: Anthony McGill, the principal clarinetist of the New York Philharmonic, took center stage at the 2015 Gateways Music Festival, playing a concerto with the festival’s orchestra. (Photo: Keith Bullis for University Communications)

When Alexander Laing was 14, his teacher showed him a magazine article about Robert Lee Watt, the first African-American French horn player to be hired by a major US symphony. Watt joined the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1970.

“I remember being excited and inspired that there was someone who looked like me, who identified as I did,” says Laing. He was then an aspiring musician, growing up in Silver Spring, Maryland. He’d begun playing the clarinet at age 11, motivated in part by his grandmother’s love of Benny Goodman.

And so he wrote Watt a letter. “I didn’t really know what to say except, ‘I’m trying to be you when I grow up,’ ” Laing says. Watt wrote back to him, a gesture that still moves him. “It was a big deal,” he says.

Today, Laing is the principal clarinetist of the Phoenix Symphony. And this summer, as he has in summers past, he’ll experience again the inspiration he felt as a teen. Reaching out to fellow African-American musicians is at the heart of the Gateways Music Festival, a celebration of professional classical musicians of African descent.

ATTUNED: “Orchestras across the country should play this music,” says Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra trumpeter Herb Smith ’91E of the pieces by composers of African descent that are part of the Gateways repertoire; classical pianist Armenta Adams Hummings Dumisani (below, left) developed the festival more than two decades ago. Paul Burgett ’68E, ’76E (PhD), chair of the festival’s board, calls her a “musical activist.” (Photo: Adam Fenster)

ATTUNED: “Orchestras across the country should play this music,” says Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra trumpeter Herb Smith ’91E of the pieces by composers of African descent that are part of the Gateways repertoire; classical pianist Armenta Adams Hummings Dumisani (below, left) developed the festival more than two decades ago. Paul Burgett ’68E, ’76E (PhD), chair of the festival’s board, calls her a “musical activist.” (Photo: Adam Fenster) (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

For young musicians, Gateways “can play an important role in just demonstrating what’s possible,” Laing says. “And how powerful an image it is. In my case, I saw one guy. I can only imagine how even more inspiring it is to see a stage full.”

The festival and the Eastman School of Music have partnered since the third festival, in 1995, with Eastman providing Gateways with rehearsal and performance spaces, along with financial backing. “Eastman has been there, quietly supporting when asked and where we could,” says Jamal Rossi, the Joan and Martin Messinger Dean of the Eastman School of Music.

But last year, Gateways and Eastman formalized and deepened their alliance. Although the festival remains an independent nonprofit organization, an intensified partnership allows the festival to raise its ambitions. Organizers are developing plans to expand the festival’s reach and increase its national and international profile, bolstering efforts to promote and increase diversity in classical music.

Paul Burgett ’68E, ’76E (PhD), the chair of Gateways’ board of directors, predicts that the effort “will have implications for American music for generations to come.”

American classical orchestras, like their audiences and administrative staffs, are still largely white. While gender disparities have narrowed among orchestral musicians over the last 40 years, for African-American and Latino players, the numbers are stagnant. Auditioning for orchestral positions is now a “blind” process—musicians, at least in the preliminary phases, perform behind a screen and even on carpeted floors, to mask the shoe sounds that distinguish a penny loafer from a high heel. But the number of musicians of African descent in orchestras, according to the League of American Orchestras, has barely budged in the last decade, and is now just 1.8 percent.

But every second summer, Gateways assembles a complete orchestra and nearly 40 chamber music ensembles from about 125 professional players of African descent. The musicians fill Eastman’s stages and fan out into the community, as soloists and chamber groups, taking their music to venues such as churches, synagogues, and mosques, private homes, community centers, youth clubs, and retirement communities. During the six-day festival, there are more than 50 performances, and the musicians play for a combined audience of about 10,000 people. And no event carries an admission fee.

STANDING OVATIONS: Concert master Kelly Hall-Tompkins ’93E (above, left), conductor Michael Morgan, and members of the Gateways Festival Orchestra rise to applause after the final performance of the 2015 festival in Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre. (Photo: Keith Bullis for University Communications)

STANDING OVATIONS: Concert master Kelly Hall-Tompkins ’93E (above, left), conductor Michael Morgan, and members of the Gateways Festival Orchestra rise to applause after the final performance of the 2015 festival in Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre. (Photo: Keith Bullis for University Communications)

With its focus wholly on professional musicians of African descent, the festival is unlike any other. “Gateways is really unique,” says Toni-Marie Montgomery, dean of the Bienen School of Music at Northwestern University and a new member of the festival’s increasingly national board.

The festival’s mission is threefold: to raise the visibility of classical musicians of African descent and heighten public awareness of their contributions to classical music; to bring musicians of African descent together, to perform together, exchange ideas, and revitalize their musical energy; and to establish role models for young musicians.

With the new alliance came the appointment of Lee Koonce ’96E (MM) as the inaugural president and artistic director of the festival. “His energy and vision will, I suspect, really move people,” says President and CEO Joel Seligman, an enthusiastic supporter of the festival who played a key role in securing Koonce and the alliance.

Koonce is the first paid staff member in the festival’s almost quarter-century history. In all that time, it has been fueled entirely by the passion of volunteers.

“It’s an extraordinary phenomenon in the not-for-profit field. I’ve never seen anything like it, quite frankly,” says William Terry, a consultant for arts and culture organizations. He’s working with the festival on its plans for the next two decades.

Armenta Adams Hummings Dumisani, a Juilliard-trained, African-American classical pianist, created the festival in 1993 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where she then lived. When Eastman hired her in 1994, she brought the festival with her.

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Dumisani as a child moved with her mother and brother to Boston, while her father stayed in Cleveland to support the family. The three lived near the New England Conservatory and Symphony Hall.

“Instead of trying to just give us lessons, they also transplanted us into an atmosphere where, every time we walked out the door, we would see people going by with violins and cellos, and we were surrounded. They just changed our surroundings,” Dumisani explained to host George Shirley—the first African-American tenor to sing leading roles with the Metropolitan Opera—in a 1975 interview on Classical Music and the African American, a show on WQXR, New York City’s classical radio station. “But at the same time, my father had a burning desire to see the race in general bettered. He wanted to see us reach great heights.”

“And so, although we were trying to advance ourselves, it had a social connotation,” she said. “There was a use for it. And I guess I’ve been trying to put those things together.”

When Dumisani arrived in Rochester, she took her efforts directly to the city’s black community. “Her studio was Rochester,” says Burgett, University vice president and senior advisor to the president. “She’d put instruments in a little grocery cart and go over to the YMCA across from Eastman—and to churches, and to schools—and say, ‘I want to give music lessons to any kids who want to take lessons.’ ”

“She created Gateways to bring together musicians of African descent because, in their training and in their professional careers, they frequently felt isolated,” says Koonce. At the same time, “her role at Eastman really was as a community advocate. So much of her work in building Gateways happened through her efforts in the community.”

Dumisani retired from Eastman in 2009 and returned to North Carolina. But the festival is deeply rooted in the Rochester community. “It’s important to me that Gateways continue to be what it is and who it is,” even as it moves to a new level of visibility, says Rossi. “It’s been built up by volunteers who, over 20 years, have been so committed to it.”

Burgett calls Dumisani a “musical activist.” Her goal, he says, was “to rely on the inner strength, motivation, and hard work of people to make this festival for themselves. If she said it to me once, she said it a thousand times: we have to do this for ourselves. The music is our music, too.”

MUSICAL HISTORY: Concert baritone William Warfield ’42E (center) performed at the festival in the 1990s. Other noted past performers include violinist Sanford Allen, harpist Ann Hobson Pilot, horn player Jerome Ashby, and pianists Paul Badura-Skoda and Awadagin Pratt. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

MUSICAL HISTORY: Concert baritone William Warfield ’42E (center) performed at the festival in the 1990s. Other noted past performers include violinist Sanford Allen, harpist Ann Hobson Pilot, horn player Jerome Ashby, and pianists Paul Badura-Skoda and Awadagin Pratt. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

That Gateways needed to be “something that we identify within ourselves, produce within ourselves, and support, not just musically but financially, ourselves—it took me more than a minute to get that,” Burgett says, “because her point of view flew in the face of the accepted wisdom about this sort of thing.”

The operative model for community-based classical music education and appreciation was the settlement movement. It emerged in late 19th-century England and arrived in the United States with the help of social reformer and Nobel Peace Prize winner Jane Addams, the founder of Chicago’s Hull House. Settlement houses were a response to growing urban poverty in the wake of industrialization and immigration—they began as organizations intended to aid and acculturate the poor through social services and education. One of their activities was teaching music. New York City’s famed Third Street Music School Settlement, founded in 1894, was the country’s first settlement house wholly focused on music. Also a product of the movement is Rochester’s Hochstein School of Music & Dance, which received its New York State charter in 1920 as the David Hochstein Music School Settlement.

“There are settlement schools all over the United States,” Burgett says. “But Armenta was looking at making it happen in a different way. She wasn’t looking for those outside, looking in, but instead trying to get those inside to look out.”

Laing says community involvement is “part of the aesthetic of Gateways. Armenta Dumisani grew the festival by joining hands with the community from the start.”

Koonce—a classical pianist who has also been the executive director of Ballet Hispanico and Third Street Music School Settlement, the executive director of Sherwood Conservatory of Music in Chicago, and the director of community relations for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra—calls his nearly 20-year involvement with Gateways “the most consistent association of my career, because, like Armenta, like the volunteers, and like the musicians who participate, Gateways resonates with me—because it was my experience, too, of being an isolated classical musician of African descent. Throughout my training and my professional life, I lived in a world where I was the only one, or one of the few.”

The festival is an antidote to that isolation. Trumpeter Herb Smith ’91E—the only African-American member of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra—says the gathering is “like a reunion, a family get-together,” while Laing likens the festival to a balm.

The musicians come mostly from the United States, but also from Europe, South America, Canada, and the Caribbean. They’re members of major symphony orchestras, faculty members at college and university schools of music, and freelance artists. And they’re selected according to their level of professional activity and achievement. “That has served us well,” says Koonce. “But it’s still challenging, and we’re working to find ways to accommodate more musicians.”

Interest in participating has been growing rapidly. In 2013, more musicians applied to take part than the orchestra could contain. The number of applicants outstripped orchestra seats by 70 for the 2015 festival. And this year, about 240 musicians applied for 120 spots.

Finding a way to satisfy that demand is one of the questions Koonce and fellow festival leaders are considering in their planning process. Not under discussion, however, is the bedrock purpose of the festival. Sometimes the spirit of Gateways is misperceived as a diversity initiative, says Koonce. “And it wasn’t founded for that purpose. While we surely want to see more people of African descent involved in classical music, Gateways is about classical musicians, who happen to be of African descent, loving and enjoying this music. The music is first.”

“The primary strength of Gateways is that it embodies the commitment of a group of musicians—in this case, musicians of African descent—to classical music, first and foremost. And their commitment to each other in their work as classical musicians,” says Terry. “The artistic quality is absolutely a strength. Gateways is always concerned about quality and will not compromise. Quality is first and foremost.”

But while the musicians in the Gateways orchestra have reached top levels of professional success, the festival exists in a world in which access to classical music isn’t equal. Children of color, as a group, don’t have the same opportunities for classical music instruction that their white counterparts do.

“I think it’s very common for black children in this country never to see a black classical player. Ever,” says Koonce. “And so we see Gateways as an institution that can offer role models and encourage children to pursue musical instruction.”

The professional classical music community is also looking for ways to intervene directly. “The field is recognizing that there’s a need to address this issue on multiple levels—and that the results could take a while to come about,” Koonce says. “In urban environments—mostly black and Latino communities, and in public schools in particular—music programs have been in decline for several generations now.”

Rossi agrees that there’s a problem in the pipeline. And to attain professional levels of success requires aspiring musicians to begin study at a very young age. “If you look at major music schools across the country, the participation rate of young people of color is very low—it’s in the single digits, 4 percent, 5 percent. And there are even fewer at the graduate level,” he says. “And if we’re not educating students of color at top programs, who do we expect to hire as faculty members?”

Part of the answer lies in casting a net wide enough to capture everyone, says Koonce. “In order to significantly increase the number of musicians of African descent in classical music, we have to have vast numbers of children of African descent learning to play musical instruments. Millions, in fact.” That kind of broad-based musical education is already happening in countries like China and Japan, and the participation of musicians of Asian descent in classical music has risen exponentially. “It’s become a part of the culture and what the culture says is important,” he says.

Years ago, music education in the United States was different. When Koonce was growing up on the South Side of Chicago in the 1960s, “every child in the third grade got an instrument,” he says. And Rochester’s public city schools were once among the finest in the nation for music, thanks to efforts by George Eastman, Eastman School director Howard Hanson, and violinist and conductor Karl van Hoesen, who taught both at Eastman and in the Rochester public schools.

Opportunity is key—on the stage and in the hall. “If we don’t provide opportunities for black and Latino kids to learn to play at a young age, we can’t expect vast numbers to go to conservatories or become professional musicians—or even become audience members. The most important factor in what influences someone to attend a classical music concert is experience playing a musical instrument as a child,” Koonce says.

Eastman is intervening locally, through a project called the ROCmusic Collaborative. Created in 2012, it provides tuition-free classical music instruction to city residents in grades 1 to 12. The program is offered in community centers in two quadrants of the city, and Rossi hopes to expand it to all four. Each student receives instruction in singing and reading music, lessons on instruments, classes, rehearsals, concert participation, needed materials, snacks and meals, and field trips.

ROCmusic was inspired by Venezuela’s El Sistema program, which harnesses music as a social force for children who have great desire and few resources. Rochester’s program was jointly developed by an array of the city’s civic and cultural institutions: Eastman, the Eastman Community Music School, the Hochstein School of Music & Dance, the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, the Rochester City School District, and the City of Rochester. Gateways has signed on as a seventh partner, and ROCmusic is aligning its summer session with the festival’s schedule, to take advantage of the partnership.More than 100 students participate in ROCmusic, and the retention rate has held at 85 percent since its founding. Twelve participants are now students at Rochester’s School of the Arts, and others are enrolled in Eastman’s Pathways program, which provides scholarships for more advanced study.

“We’re starting to feed the pipeline,” says Rossi. “But this is a 30-year commitment.”

James Norman is the vice chairman of the Gateways board and the president and CEO of Action for a Better Community, a Rochester-based community action agency, one of a network of such agencies established by the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 to fight poverty. He’s also the brother of renowned opera singer Jessye Norman.

When traveling with her for performances in the United States and abroad, he’d look at the orchestras that accompanied her. “You may spot one or two people obviously of African descent. And it raises the question, why?”

The Gateways stage, he says, offers a different vision. “In order for people to aspire to things, it’s good if they can see themselves in that thing. And Gateways is a way for African-American youth, and youth of color, to see themselves. To see the possibility.”

“You have to know there is a route for you,” says Rossi.

In past years, Gateways gave young musicians an opportunity to participate, with their own concert at Rochester’s City Hall. This year, the festival is offering a pilot program called Young Musicians Institute. Young people from music programs in Rochester will spend a day and a half with Gateways musicians, attending an open rehearsal and then joining them onstage at Kodak Hall to play along with them. Later, groups of Gateways musicians will “adopt” Rochester community-based music organizations to establish year-round relationships.

The musicians are meeting the plan with enthusiasm. “We all know how important it was for us to see someone who looked like us playing this music and these instruments,” Koonce says. “That’s why our activities with young musicians are so essential to us.”

In its performances, Gateways blends standard repertoire for orchestral and chamber group performance with pieces by composers of African descent: composers like Florence Beatrice Price, who became the first African-American woman to have a composition performed by a major symphony orchestra when her Symphony in E Minor was performed in 1933 by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. And Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, whose work brings together classical music and jazz. He was the cofounder, in 1964, of the Symphony of the New World, the country’s first racially integrated orchestra, and a Gateways participant before his death in 2004.

LOOKING AHEAD: Pianist Lee Koonce ’96E (MM) is the first president and artistic director of Gateways. He says his experience as a classical musician of African descent was one of isolation. “There’s such an intense conversation right now about diversity in classical music,” he says. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

LOOKING AHEAD: Pianist Lee Koonce ’96E (MM) is the first president and artistic director of Gateways. He says his experience as a classical musician of African descent was one of isolation. “There’s such an intense conversation right now about diversity in classical music,” he says. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

Audiences clearly value the inspirational nature of the festival, according to surveys and other feedback. Barbara Jones, cochair of the festival planning committee and a retired vice president at JPMorgan Chase, says that while the Rochester community is strong in arts and culture, it hasn’t always been very welcoming to people of African descent, particularly in classical music. “Gateways has changed the face of classical music in Rochester—our audiences see that, and they understand and appreciate that people of African descent have been involved in classical music for centuries,” she says. “It’s just something that hasn’t been celebrated or noted.”

For the musicians, taking to the stage with other musicians of African descent can be deeply moving. “I’ve been the only African American in the Rochester Philharmonic for so long, it doesn’t even faze me,” says trumpeter Smith. “I’m used to it. But when you’re in the Gateways orchestra with all people who look like you, it’s an amazing thing. It really is.”

The experience, says Laing, “strengthens, it enlivens, it prompts inquiry.”

Ultimately, the inclusivity of professional classical music turns on choices that lie beyond the reach of any single performer. And the field of music can do more to change things than wait for young children to reach the age of professionalism, says Laing. He draws a contrast between the music world and that of athletics.

“In professional sports, they’ll scour the Earth to find the players that they need. Is there more that the music field could be doing? Absolutely, if it wanted to. Sports will find the athletes they want and recruit them to their sport because they see in them the potential for what they could be. They see the potential for that person or persons to help them succeed toward their goals. They don’t necessarily just wait for them to come to tryouts. The question is, what are our goals?”

Smith sees changing the demographics of orchestras in similar terms. “It’s not just a quick thing,” he says. “It’s more a commentary on society and what people deem important.”

With consultant Terry’s help, the directors and volunteers of Gateways are looking ahead 20 years, giving careful thought to how the festival can contribute to answering those questions.

“Gateways has a very focused founding purpose, but Gateways is embracing of large communities,” Terry says. The organizers want people “to hear this music, to engage with these musicians. Gateways started with a narrow focus that in time will be able to expand wider and wider.”

Central to that aspiration is making the festival an annual event. As a biennial festival, says Terry, “it’s as though the organization is reborn every two years.” The process will be gradual because of the challenges of raising the needed funds, but all agree that a yearly festival will give Gateways greater visibility and momentum. And it will help organizers to meet the demand from musicians who want to participate.

The hunger for community isn’t exclusive to musicians of African descent, says Burgett. Professional classical musicians devote their lives to an endlessly demanding program of training and practice. It’s common to feel some isolation.

But for classical musicians of African descent, “there is the added burden of race, so even when you go out into the performing world, especially if you’re an orchestral player, that isolation and loneliness persist,” he says. “When these musicians come to Rochester, there’s a deep sigh of relief.”

Dumisani pushed her cart full of instruments through Rochester streets in response to that loneliness—to draw more performers of African descent to classical music, to help them discover what the music could add to their lives and how they could contribute to changing the musical world.

“When we wish upon a star, someday this won’t be necessary,” says Burgett. “We will have perfected our efforts at creating a better world for all people, and the hunger—and that’s what it is, it’s a hunger—that the musicians bring to the festival will be satisfied.”

The 2017 Gateways Festival will be held August 8 to 13, with a final concert under conductor Michael Morgan. The program includes Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto, performed by Canadian pianist Stewart Goodyear, and a performance of Rochester native Adolphus Hailstork’s An American Port of Call. For details, visit Gatewaysmusicfestival.org.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)