African American Troops Organize in New Bern, NC 1863

by Hari Jones,Richard Sauers,and othersAfter the fierce confrontation on March 14, 1862, the Union Army chose the North Carolina city of New Bern (or Newbern), first settled by Swiss and German immigrants in 1710, as its base of operations in the region. Thousands of escaped slaves congregated in New Bern and the surrounding area, making it a symbol of emancipation and key recruiting ground for the U.S. Colored Troops.

Just over 50 percent of the New Bern population of approximately 5,400 was African American, with just over 700 of those individuals being free persons of color. According to a census conducted by Vincent Colyer, who was appointed “superintendent of the poor” by General Burnside in March 1862, there were 10,000 African American refugees in the Department of North Carolina, with 7,500 in New Bern and its surrounding area. This number would continue to increase for the duration of the war.

Most whites fled the town as the Yankees moved in. Those who remained were loyalists or those who didn’t care one way or the other, and only wanted to maintain a living. Soon after the Federal occupation, hundreds of contraband slaves began to congregate in the area, changing the demographic composition of New Bern. In New Bern,General Burnside also found a very friendly African American community eager to provide information on Confederate activities. Also, one of the leading citizens of New Bern, Edward Stanly, was a Unionist who became the provisional governor of North Carolina in 1862.

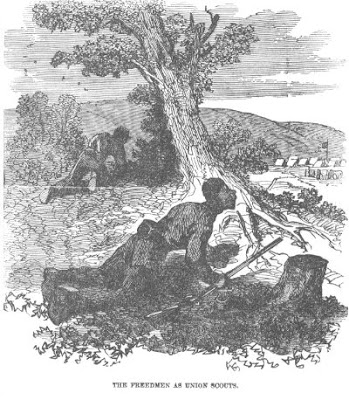

One Union soldier referred to it as a “Mecca of freedom.” It also became a headquarters for covert activities being conducted by African American scouts, spies and spy handlers. After General Benjamin Butler gave “fugitives” refuge at Fortress Monroe in May 1861 and the influx of refugees on Roanoke Island in February 1862, Burnside was aware of the likelihood that he would get a substantial number of refugees, especially since he had the reputation of dealing with them fairly. He appointed Vincent Colyer to attend to such affairs soon after occupation began.

Newbern was a Mecca for escaped slaves. The Union command did not anticipate such heavy contraband escapees and was initially unprepared for it. Military governor Edward Stanly tried to enforce state law regarding slaves and came into conflict with abolitionist soldiers and officers, as well as a major conflict with Vincent Colyer, which caused a political uproar in Washington, D.C. Eventually, Union aid societies assisted the freedmen in learning to read and write, and created James City to house the freedmen.

The Union Army was able to hire a work force that performed critical combat service support tasks, such as building fortifications and unloading supplies from ships. African Americans who would become soldiers and laborers learned to read and write in New Bern’s Freedmen School, which was established in April 1862. Also, African American artisans were very successful in the city working privately and for the government. These African Americans combined with the free population that had lived and prospered in the city prior to occupation would make New Bern an important commercial and cultural center for free and freed persons of color in North Carolina.

Thousands of freedmen joined the Union Army and Navy. The 1st North Carolina Colored Infantry (35th U.S. Colored Infantry) was first organized in the spring of 1862 in New Bern by William H. Singleton, a runaway teenager from Craven County who had initially volunteered to be a manservant for a Confederate captain.Recruiting for the African Brigade is progressing lively and enthusiastically," wrote Corporal Z. T. Haines, of the Forty-fourth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, in late May 1863. "Quite a recruiting fever has seized the freedmen of Newbern. ...Four thousand colored soldiers are counted upon in this department." At almost the same time another soldier, William P. Derby of the Twenty-seventh Massachusetts Volunteers, recorded the excitement within the city's black population. "One can hardly forget the enthusiasm amongst the negroes of this place, placards being posted around the city, calling for four thousand men for 'Wild's colored Brigade.' Street processions of the most motley character were the order of the day."

However, the regiment was not mustered into Federal service until June 1863. Singleton and other U.S. Colored soldiers recruited out of New Bern, like Furney Bryant, were outstanding guides, scouts and spies. The most successful Union generals would learn from the Union experience in North Carolina that African American soldiers with knowledge of the local terrain made outstanding guides, scouts, spies and raiders. General Grant would call the African American soldier a “powerful ally,” and a regiment credited to the state of North Carolina, the 36th USCI (originally the 2nd North Carolina Colored Infantry), was among the first Union troops to enter Richmond.

On June 30, 1863, the 35th United States Colored Troops regiment officially mustered in New Bern.

The organizing and recruiting of North Carolina’s African American troops had already been underway for nine months. In July 1862, Congress issued a Second Confiscation and Militia Act. The act allowed President Abraham Lincoln to use as many African Americans as he deemed necessary to suppress the South, and to use them in whatever way he thought best to accomplish that end.

The use and treatment of African Americans varied, and men were frequently assigned fatigue duty rather than combat. However, Lincoln did authorize African Americans to assume combat roles in the January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation.

That May, General Orders No. 143 established a Bureau of Colored Troops and all future regiments would be designated as United States Colored Troops.

North Carolina units began organization under the Corps D’Afrique designations and as state-named regiments, but entered into service under United States Colored Troops designations.

Combined with the Trent River Settlement, renamed James City, the New Bern area remained an important symbol of emancipation and a model for rehabilitation and/or assimilation into a free society. Chaplain Horace James, for whom James City is named, assumed responsibility for the freedmen in the area in 1863 and became the superintendent of the Freedmen’s Bureau in North Carolina. His experience in New Bern would influence his activities throughout the state. African American artisans and businessmen of New Bern became leading citizens beyond Reconstruction. The African American community in New Bern became very active in self-governance until the rise of the “white supremacist” movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. New Bern and the rest of North Carolina would subsequently fall victim to racial hatred and discrimination.